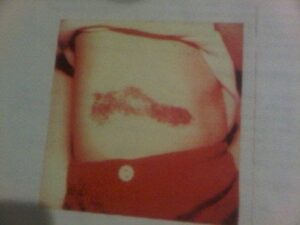

When looking for a title for this piece I googled synonyms for “rare.” AVMs are rare in general, and mine might be a little more rare than expected. I have two and neither are in my brain. One is in the left side of my neck and the other takes up the majority of my right torso. That torso one was immediately visible upon my birth. A purple-ish, red-ish cluster of blood blistery looking bumps in the shape of a shoe (by my estimation).

These pesky little bumps used to bleed anytime they rubbed against my clothes. It was a problem. It was also the 1980’s, and AVMs weren’t exactly common knowledge. A plastic surgeon removed “the shoe” when I was 7 years old. What no one realized at the time was that he cut into the internal portion of the AVM thus starting it on a path to grow out of control. AVMs are slow-growing, so I didn’t notice much of a problem until I was 13, when my belly swelled up one day. My parents took me to a specialist at Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago. That doctor knew what it was, but he didn’t know how to treat it. We left knowing it was there and that it would swell and hurt, but there were no known options for treatment.

Fast forward almost a decade when I began having consistently terrible stabbing pains in my back. Upon prompting from a medically curious friend, I went to a doctor who ordered an MRI and discovered the aftermath of that shoe surgery. The shoe, internally, was now a mass of tangled vessels creeping into my back and abdomen. It was huge. Now, however, we discovered a doctor who was treating these AVMs with ethanol embolizations, Dr. Wayne Yakes at the Vascular Malformation Center in Colorado. During my consultation, he told me that my AVM was the second-largest he had seen. In order to get it to a stable place, I would need monthly treatments for approximately 3 years. He underestimated.

These treatments are not easy. They require intubation, anesthesia, and several injections of ethanol directly into the vessels. There is a 9-12 day recovery period after each one filled with steroids and painkillers. I didn’t live in Denver so I had to fly to and from my home. I would do these trips on my own because no one could take time off every month to accompany me out of state for these two-day surgeries in the middle of a week. At 27 years old, though, I decided this treatment schedule would not stop my life trajectory. I tried to keep my job in corporate America. I tried to keep performing as a singer-songwriter. I tried to keep my relationships intact, and I continued going to school for my masters degree. I fooled myself into believing I was invincible. My body, however, put me in check.

A few months in, I developed a wound that would not heal, and I became very ill. My doctors told me I had to stop everything to focus on my health. I had access to a disability insurance policy through my job, but the bigger issue was how would I have health insurance without my job. This was before the Affordable Care Act. The person I was with at the time was able to put me on her policy, but because of the switch, I had to go through the process of treatment approval all over again.

I know I’m preaching to the choir when I tell you insurance companies hate AVMs almost as much as those of us who have experienced them. AVMs require expensive treatments, and because AVMs are rare, there are limited specialists to treat them. My battles with health insurance companies began when they stopped paying my doctor for pre-authorized treatments about a year and a half into the journey.

I fought the good fight, but stress takes a toll. The battle with the insurance company went on for 9 months, and during that time, my treatment was on hold. When we finally reached a resolution and I returned to Colorado, my pre-surgery blood work exposed a new challenge: Leukemia.

Time has been a blessing for me in all of this. Prior to 2001, Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) was a virtual death sentence after two years. There was no effective treatment. However, by 2007 when I was diagnosed, a daily oral chemotherapy drug became available that changed this cancer to a chronic condition. For most people, this daily drug controls leukemia. It is not a cure, that still does not exist, and the medication has its side effects, but so long as my leukemia doesn’t mutate and my body doesn’t resist the drug therapy, I can survive with this. Having already learned to live with a chronic condition helped me with the acceptance process of this second issue.

Once the leukemia numbers were trending down on the medication, I returned to AVM treatment for another 3 years. In 2010 Dr. Yakes believed my malformation was in a stable place, and he released me from my monthly treatment schedule. I felt free. I would only need to do an MRI once a year to make sure there were no changes.

Returning to life not revolving around trips to Denver every month, however, was challenging. First of all, I thought I would feel significantly better. I soon realized some of the side effects I was chalking up to the ethanol embolization treatments were actually side effects from the leukemia medication. I wasn’t on the steroids and painkillers from the AVM treatments to help mask the leukemia issues, so now I had to confront those. Second of all, I lost the constant connection to a medical facility that totally understood my condition. I was on my own answering questions about AVMs to new doctors who had no real understanding of something so rare and found me fascinating. I developed an elevator pitch-length monologue about what causes vascular malformations, the procedures to help them, and my experience, that even now I have to trot out frequently. Third, my finances were in shambles. By 2010 the great recession had almost tripled the interest rates on my credit cards that I used to pay for the travel, lodging, and exorbitant co-pays for both the leukemia medication and AVM treatments because my savings had been completely depleted.

Living with chronic conditions has a learning curve at all stages. Not being in active treatment makes people think you’re completely fine and that everything is over. You and I know better, but how do we help others understand? There is also a question about when and when not to “come out” about having an illness. I personally avoid telling anyone new who I perceive might give me the pity head tilt. Also, the goals for our lives might shift many times while living with these conditions. We don’t stop being who we are or wanting what we want out of life, but we have to prioritize and find other avenues to reach the goals most important to us. The biggest lesson though is learning to have flexibility in our lives for the times when the chronic nature of conditions choose our paths for us. That last one was a struggle when my 2018 MRI showed the AVM was again growing and I would need to return to treatment.

Nearly 9 years after I left, I returned to The Vascular Malformation Center as someone in a totally different part of her life. I’m in my early 40’s now with a spouse and a young child. I no longer feel the invincibility of my 20’s. I know what to expect and exactly how much of a toll it will take on my life, and the lives of others.

After the June 2019 treatment, I realized how blinded I was that first go-round, by constantly looking towards the future and not acknowledging the difficulty of the present. I decided for myself that now I would need to negotiate how often I returned instead of trying to ram through to the end at a breakneck pace. Accepting that this AVM and the CML are not something to hate and focus on destroying, but rather acknowledging them as the difficulties they are and making space within my being to co-exist is a continuous lesson in emotional growth.

Click the photo to learn more about Erin Havel.