I found my vocation as a special educator on the first day of summer camp in a park during a tornado. It was 1976. I was 15 years old. Spending three hours in a public bathroom with eighteen unique five year olds and a bunch of committed adults made me realize that I was meant to do this. We sang songs, calmed fears and corralled the children, and I loved it. When I went back eagerly the next day, I knew I was in for life.

Forty years later, a storm inside my brain nearly took it all away. The storm was a ruptured aneurysm requiring clipping. I awoke with that “life headache” in the middle of the night. Luckily, my husband heard me, found me moaning in bed and called 911. The ambulance rushed me to the hospital, which sent me to another one – BIDMC. Doctors at the first hospital felt confident that BIDMC (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston) is the best place to be for neurosurgery. I had two small strokes during surgery, spent ten days in ICU and four in step-down – most of which never made it into my long term memory. I was then transferred to inpatient rehab with a very fuzzy concept of time, having just come to the awareness that I’d had brain surgery when I looked in the mirror and saw the scar spiraling from my forehead to the middle of my scalp. I needed help putting all the pieces together.

I have always lived my life in the rhythm of a school schedule and expected to continue doing so until my retirement five years in the future. The last day I remembered was the Monday of school vacation week, which kicks off with Marathon Monday, a big deal in Boston. I was sure that I’d be returning to teaching after break to deal with the crazy end of school, IEP team meetings and last minute evaluations – maybe needing a few sick days. I had no clue that there had been a substitute in place for a week, with a plan for her to finish out the year in my stead.

The work at inpatient therapy was the work of life skills, and it soon made me realize what a long journey I had ahead. After my first speech therapy session, I asked my husband to review the timeline from the rupture to the present, a request I would make repeatedly for quite some time. I needed to hear and understand what had transpired, because it was all a big blank to me. It was so hard to believe that I’d lost two weeks. I also requested that the case manager give me the specific goals and objectives I’d need to achieve for discharge. Still, I maintained the fantasy of a speedy recovery so tightly that the neurologist had to sit me down for a harsh reality check – that at minimum no one returns to work from a rupture and clipping before six to eight weeks of recovery.

Even in my storm-scrambled brain, I realized that six to eight weeks from that moment would be the end of the school year. And, while part of me was panicked by that realization, a little piece was guiltily relieved. I’d started to become aware of my limitations and how easily I became overwhelmed. My job as a resource teacher entailed multiple roles. I was an interventionist, a consultant, a team chair, an evaluator and an educator. There were so many pieces to keep track of, and I couldn’t even sit down safely in a chair while attempting to use the TV remote control.

My principal had helped my husband through the FMLA paperwork process, and I had banked over three hundred sick days, so the financial pressure was not immediate. I had the luxury of focusing my energy toward recovery. Cards began arriving from friends, colleagues and students and each was bittersweet. I missed “my kids” and worried about them, but didn’t have the capacity to process the details or provide support to the team of substitutes in any concrete way. When the principal called with one specific question about where to place my student with Down Syndrome for the following year, my anxiety went into overdrive. I was able to give her the information, but at a cost. It scared me so to have to respond on demand, and I knew I had a lot to conquer.

And so, the following two weeks were spent becoming a semi-functional human being. I relearned how to walk stairs, take a shower, and get in and out of a car. I learned strategies to support my short term memory and word retrieval. I began using my phone – with some “interesting” text messages and emails sent to a variety of people. My resource partner sent an email to my husband that she had received a blank text and an email with “a couple of words and then random letters”. Rick sent a group warning that I was attempting to communicate, but my fingers couldn’t keep up – and he was not about to take my phone away (as if he could). I had therapies for at least three hours daily and dreamed of being home. I made progress toward my documented goals – walking stairs, getting in and out of the shower, finding my verbal vocabulary and incorporating my left side into everything. It culminated in successfully and proudly making a plate of scrambled eggs for the OT, and then it was time to go home with my husband, who would lovingly serve as primary caregiver and chauffeur for the next stage of recovery.

I was immediately faced with a teacher decision. On the night after I got home, there was a dinner to present awards from students and their families to people who “made a difference” for them. I’d been nominated by one of my girls and decided that I had to go so that she would feel acknowledged. As it turned out, that was a case of “too much, too soon” – a noisy school cafeteria, lots of people and verbal interaction, warm greetings and hugs. My award was presented first, I spoke briefly with the Superintendent, who acknowledged my level of commitment. I then hugged Erika and her mother to thank them, posed for a quick photo, and Rick whisked me home to bed.

June was a surreal month of outpatient therapies, company, a school picnic and a visit to my classroom to see and be seen. The children (and adults) had all kinds of questions, lots to tell me, and another big round of hugs. I took a couple of tearful rest breaks, but it went very well. I was told that it had taken parts of four people to fill my shoes. I knew that I’d been a talented juggler, but would I be ready to do it again in September? Once again, it was time to roll up my sleeves and do the work.

Task analysis, the bedrock of special education, stood me in good stead for this phase. I identified the aspects of returning that would be most challenging, and my very creative therapists helped me address them. Speech/Language therapy sessions dealt with distracted listening, reading comprehension, note taking and summarizing. Physical therapy built my strength and stamina and had me navigate a simulated first grade classroom while interacting with whomever spoke to me. Stools were pushed into my path, a game of catch took place in front of me, and the PT did a very good imitation of a first grader who needed to know when we were going to recess. Occupational therapy was the most challenging. We were still working on integrating my left side and on getting me ready to drive again.

Rehab was approached with desperation, borne of fear. If I couldn’t go back, who was I? I’d been a teacher all my life. It was my anchor, my heart, my identity. And, it was my financial security. I was so close to a full pension, but our financial future would be bleak if I couldn’t get there. There was no other choice – I HAD to go back. I wanted to go back. I needed to be Mrs. Losk again.

I graduated from my therapies, was cleared by my doctors to return full time, was able to drive by mid-August, and so the concrete planning began. The doctor had documented specific accommodations I would need, and I met with my principal and the other special educators to allocate caseload assignments. Most of my students were familiar to me – my second graders who’d moved on to third and my first graders, now in second. The aide working with me had been “my other half” for many years. With the exception of the new third grade math curriculum, everything I needed to do was stored in my unimpaired Long Term Memory. I was set up for success, but had no idea what the reality would be like. I was equal parts excited, terrified, proud and uncertain.

Labor Day came quickly, and with it came back to school jitters at a brand new level. I was returning to the place that had been my professional home for twenty eight years, but I was not the same Mrs. Losk. My passion for teaching was as strong as ever, but the way I interacted with the work was dramatically different. I was more vulnerable, but more determined than ever. I had no idea how it would feel to be back in that world, where I’d been a go-to resource. And so, with gratitude and trepidation, I agreed to read aloud the Maasai anecdote that always set the tone for our first staff meeting. The Maasai greet each other with the question, ‘How are the children?” believing that is an indication of how society is doing. As I stood before my colleague-family, paper shaking in my hand, I heard sniffles, murmurs and, when I finished, applause. I’d cleared the first hurdle! Woo Hoo! But there were so many more to come.

And so began the hardest semester of my life. I was eager to get started with the children and to TEACH again. And there were lots of wonderful moments when the children were well – successful lessons, creative flashes, connections made and reestablished. But, often, I was overwhelmed. Everything came at me at a furious pace. I carried a notebook everywhere and asked people to send me reminder emails for most things. Holding on to things in short term memory until I got back to my office was not an option. The Mrs. Losk who could do it all wasn’t there. My brain was strong and worked well, but with constraints. I couldn’t chair a Team meeting while writing the IEP any more. I couldn’t come up with an entire lesson on the fly when needed. I could do anything, but not everything. By the middle of the first week, that was clear, but I still hoped it was just rust. After all, I’d overcome so much by being stubborn and working hard – surely this would come back too.

I needed to spend more time planning, but had nothing left for working when I got home. I became what we referred to as a “lump on the couch” every late afternoon and evening. As a result, my anxiety skyrocketed and impacted my sleep. Stuck in the vortex, I became more and more exhausted. I was doing the job – generally competently – but the cost was profound. When Thanksgiving weekend did nothing to restore me, I knew. Hoping against hope, I went to Amy, my principal and friend. “Is it the job or is it me?” Amy is never anything but honest, still her response cut deep. “It’s you. It’s too much. I’m so sorry,” I couldn’t fight it anymore. We decided that I’d spend time documenting everything I could until winter break – no one was going to have to figure it out on the fly this time. And so, after many, many tears, I was ready to let go.

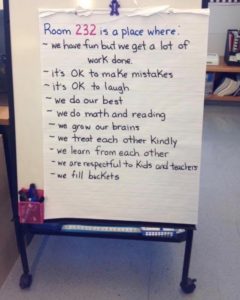

My proudest moment came when I asked the children what they wanted their next teacher to know. They generated this list, and I knew they would be well.

There were lots of tears and hugs and promises to visit, but I had no idea of what was coming next. The financial insecurity was great, and the awareness that I might never return was greater. But, at that moment, all I wanted to do was rest.

It took a full month to get back to a functional level, but I did, and my broken heart began to mend as well. I arrived at a new, more rational place and began to plan. With more than a year of sick days still remaining, I had the option of taking that year as a medical leave, bringing me closer to my retirement goal and security. But that was not the way I wanted to go out. I wanted to be Mrs. Losk, to answer that “the children are well”, to “have fun and get work done.” But being a teacher had to fit with the new me, rather than the futile struggle to make my new self reach the level of pre-storm functioning.

And so, we came up with a plan. It was a process of intense negotiation, many meetings, creative thinking and powerful advocacy. I knew that four days was all I could manage. There was no Special Education position to fit that schedule, so it was agreed that I would be an interventionist in the primary grades, providing a safety net to many of the at risk students. My skill set would apply and I would spend my resources on direct instruction. My drive to provide as much value as I could, rather than take full sick time was valued. No one doubted my commitment – demonstrated early at the “too much, too soon” dinner and by the semester I had worked – and the difference I could make for some vulnerable kids.

I spent the spring and summer preparing. I went back to Physical Therapy to develop strength and stamina and did my home program every day. I made myself a work space at school, across the hall from Room 232, which was occupied by the special educator who had appeared at just the right moment to take my role. We sketched out my schedule – Monday through Thursday from 7:30-1:00. I would begin with an individual student before the school day, and consecutive math groups during the day. As often happens in a public school, a new, at risk student had moved in. She was a second grader needing intensive reading instruction and she became one of my girls. Working with her so closely was a joy; hard work yielded steady progress. The whole experience of being able to focus on and connect with my students and to experience successes, soothed my heart.

I was an interventionist for 18 months before I retired on my fifty eighth birthday in December 2018 – earlier than the pre-rupture plan, but financially feasible. I’d come back to feeling like a teacher again and was able to end my formal career feeling fulfilled, successful and joyful. Retirement was a process and an overwhelming outpouring of love in many forms acknowledging and validating my impact and my effort. Since then, I’ve volunteered as a consultant and done a bit of tutoring. I’m proud to have earned the right to say that I will always be a teacher. I’ve accepted the different me, with limitations, constraints and tenacity I didn’t know about. Forty years out from the first tornado and four years out from the storm that nearly took it all away, Mrs. Losk’s teacher’s soul has found peace.

Click the photo to learn more about Beth Losk.