Physician, heal thyself: What I learned as a clinician from being a patient

The year was 2014. The patient, a 21 year old female, presented to the ED complaining of a sudden onset headache – “The worst in my life” she says, in between retching and vomiting the last thing left in her stomach. She was unable to touch her chin to her chest – neck stiffness – and was feeling quite sensitive to the lights. ‘Thunderclap headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, vomiting… must be a subarachnoid headache’ I think to myself. I had done three years of medical school already and, having had a ferocious passion for neurosurgery since I was six, remembered the many patients I had seen before her with the same presentation. She is ushered into a bay and given an intramuscular anti-sickness injection – ‘Ah yes, the technique they taught us to avoid the sciatic nerve’ I thought as the nurse injected it. The patient slips in and out of consciousness as she is wheeled to the CT scanner, after which she is told she has had a subarachnoid hemorrhage. ‘I was right!’ was my first thought. ‘Wait, that’s not a good thing’ was my second.

For you see, I was the patient.

Your mind does strange things when faced with an unexpected situation. As it turned out, mine was just hardwired in medicine mode. I instantly thought of the first neurosurgical case I had seen – a young woman who had tragically lost most of her brain function about 24 hours after she was admitted with a subarachnoid hemorrhage. I felt like that was where I was headed. “Well, goodbye then. It’s been fun” I said to my boyfriend, who had taken me to hospital. At least, I thought I said it. He denies this.

As you’ve probably guessed, that was NOT where I was headed. Thankfully, I went to a specialist neurosurgical hospital instead. My family and I were told that I had suffered a rupture of an arterio-venous malformation (AVM – an abnormal tangle of blood vessels) which had caused a bleed in my brain. What followed were many confusing weeks of time standing still (apparently I believed that every day was Wednesday, when asked). But despite my confusion, I was still somehow in “medical student mode” – My family tell me that I was asking to see my observation charts, assess my own neurological exams, tried to interpret my scans, and question why nobody had tested me for “dysdiadochokinesia”, even though I didn’t know what day it was. Medics well and truly make the worst patients!

It was during this initial admission did I learn my first important lesson that I carry with me to this day – Patients never get to see their doctors enough. In my pre-AVM life on the wards, it felt like all I did was see patients. Every minute spent was seeing patients, and I thought the converse was true – patients would see doctors all the time. To my disappointment as a patient, this was actually not the case. Save for the brief ward round you get in the morning, probably only 1% of my day was spent talking to a doctor. The rest of the time I was just wondering when I got to see a doctor, wondering when I could get my next dose of painkillers, or wondering why people kept telling me it wasn’t Wednesday – were they stupid? Of course it was! I now understand why on ward rounds, patients often are overflowing with questions or concerns. Doctors, please try not to get irritated – we only see you for about 5 minutes a day. Those 5 minutes shape how the rest of the day feels to us and to our loved ones.

The other important thing I realized was that nurses and health care assistants (HCAs) are true angels. I have so, so much respect for them – there was a point where I wasn’t able to go to the toilet or shower and (embarrassingly) needed either bed baths or bed pans. The nurses and HCAs helped with these basic human needs with a smile, assuring me it was nothing to be ashamed of. You form a very strong bond to the nurse looking after you – even stronger than with your doctor sometimes (sorry doctors!). So herein lies lesson two: Nurses are amazing, and they know their patients. If a nurse tells you they’re worried about a patient – listen to them. They are often their best advocates. And medical students – nurses are excellent teachers, make friends with them and your placements will be so much better.

Something I have come to appreciate as a patient that is never really highlighted as a med student is how onerous the process of recovery is. I swiftly realized that being in hospital, recovering from the initial rupture – that was the easy and straightforward bit. In the hospital I had help from the nurses, doctors, HCAs, porters, kitchen staff – in the hospital I felt safe. The hard work really began after discharge. I can understand now why my patients are often reluctant to go home and whenever I am counselling neurosurgical patients I see at work, I try to be realistic with them about how tough recovery at home can be, and how important it is to ask for help. Recovery is a marathon, not a sprint!

Asking for help is not just for physical needs either. I went through a very apathetic phase where I wasn’t enjoying anything, I felt listless, I felt like there was no point in continuing with my studies when everything about me had been taken away. Of course, being the conscientious medical student that I was at the time, I realized that I was sinking into depression and asked my neurovascular specialist nurse for a referral to neuropsychology. After a long and arduous psychological assessment, I was found to have mildly reduced cognitive function – but not enough to impair my life. I will never forget the words the neuropsychologist said to me after my assessment: “Perhaps you need to consider a new career. I’m not entirely sure if you’ll be able to be a neurosurgeon anymore”.

I spent the rest of that day crying in the toilets.

It took me a very long time to accept that life after my rupture was, quite frankly, never going to be the same. I asked for a referral to therapy which was all focused on acceptance of what had happened to me. It was hard – perhaps one of the hardest things I have gone through – but absolutely necessary and I am so glad I did it. Whenever I see patients who consistently appear to be down about their situation, I feel compelled sometimes to be sensitively frank with them: Yeah, this situation utterly sucks. It really, really does. But until you accept that life is never going back to what it was before, and yeah this is your new normal – you’ll never truly be able to start psychological recovery in earnest. I sometimes get survivor’s guilt when I see how badly some of my patients are affected by their AVMs and aneurysms, guilt about the fact that I got off very lightly. And sometimes I will come home and cry to my husband when I see some patients that are so similar to me, but have come off far worse. However this continuous reminder at work about how devastating the impact of these conditions can be is what makes me strive to become a neurovascular neurosurgeon and to promote patient education and patient advocacy as much as possible.

Suffering from a ruptured AVM has been utterly miserable – but it has opened several doors for me! I believe this has made me a better doctor. I’m sure some patients won’t believe me, but when I say “This is tough, I know what you’re going through” – I really do! I have also been fortunate enough to become trustee of a charity called Brainbook, which is a charity run by neurosurgeons and is dedicated to promoting patient, public and medical student education about neurosurgical conditions and procedures. We create easy to understand, easy to access resources on our website and social media – I even wrote an article all about AVMs! I recently had an angiogram where a fellow trustee happens to work – so I decided to get it filmed to show patients who are anxious what an angiogram is REALLY like. It’s still being edited, but keep an eye out on the Brainbook YouTube channel to check out yours truly!

If I were to summarize what I’ve learned, really the main point would come down to this: Asking for help is so important. I try my best to encourage my patients to ask for help as much as they can – not just physically, but also mentally. This is a life changing event that WILL affect you and everybody around you. There is absolutely no shame in asking for help – believe me when I say that it can come from many different places that you never even thought about. Appreciate your victories – no matter how small. As a doctor, my small victories were a thank you from a patient, a diagnosis that my seniors agreed with, a good cup of tea. As a patient, my small victories were going to the toilet by myself, successfully making a cup of tea, being able to read AND listen to music at the same time. As I said before – recovery is a marathon, not a sprint, and marathons can only be completed by continuing to look forwards.

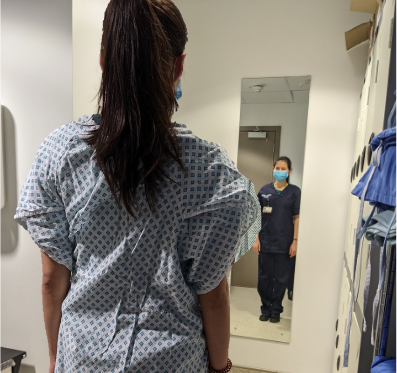

Click the photo to learn more about Dr. Gwenllian Evans.